This blog post is written by Director of Restorative Practices and Culture, Megan Ave’Lallemant.

Healing-centered engagement offers an important departure from solely viewing young people through the lens of harm and focuses on asset-driven strategies that highlight possibilities for well-being. An asset-driven strategy acknowledges that young people are much more than the worst thing that happened to them, and builds upon their experiences, knowledge, skills, and curiosity as positive traits to be enhanced.… Healing-centered engagement has an explicit focus on restoring and sustaining the adults who attempt to heal youth—a healing the healers approach.

—Dr. Shawn Ginwright

“What were you like in middle school? What was school like for you?”

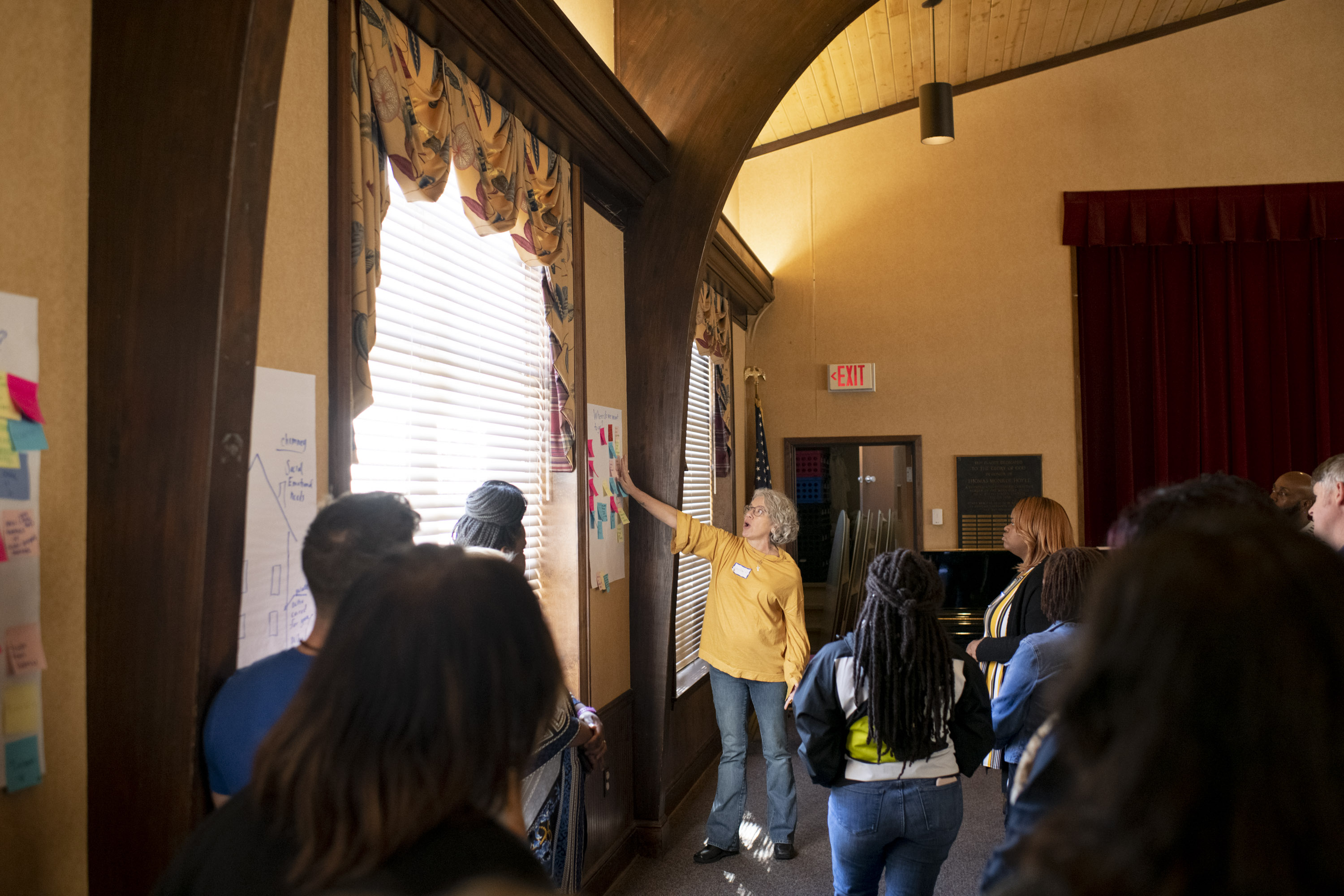

We asked these questions to a group of teachers, administrators, nutrition specialists, paraprofessionals, students, and parents gathered at Hubert Middle School for a day-long workshop. This is where we started—personal stories.

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

Deep Center’s Healing Schools Initiative

Why were we doing this? The workshop marked the beginning of a partnership between Deep Center and the Savannah Chatham County Public School System (SCCPSS). The initiative, called Healing Schools, uses grassroots community engagement to incubate a new model for school climate and culture that is grounded in the values of restorative justice. The Healing Schools model empowers students as learners and leaders, and engages teachers, staff, families, and young people as collaborators in the development of policies that support positive responses to school discipline, calling young people into community rather than pushing them out.

Because of Deep Center’s long history partnering with Hubert Middle School, and because of the Hubert staff member’s eagerness to work from the ground up to build a new toolkit for school climate, Deep was thrilled to choose Hubert as Healing Schools’ first pilot site.

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

Humanizing by Recalling

Which brings us back to why we are all sitting in a Presbyterian church hall on a Saturday morning, asking ourselves to remember what it was like to be a young person. At Deep, we know that connecting on a personal level makes our work together richer and more meaningful, and this time was no different. If we can begin to see the middle schoolers who still live on inside the adults—young people who were theater stars, math-lovers, struggling at home, getting Cs, acing tests, hurt by their teachers, healed by their teachers, considered “a problem”—we can better recognize the humanity in our own young people and their own nuanced realities.

As folks shared their stories, they also began seeing their students—especially those whom they found most challenging—in a new light. We continually challenge the deficit-language of “bad kids,” speaking of them instead as young people coping as best they can with the tools they have. “Behavior is indicating a need,” our guest co-facilitator Jason Seals reminded us. Jason teaches in Oakland, California, and has done radical healing work with school systems, juvenile justice systems, and universities. His wisdom guides us always to remind ourselves to think about a little baby who cries. We don’t tell that baby to “deal with it”; we ask what’s needed. That doesn’t change as young people age. Our job as adults is to figure out what’s needed, help the young person identify it, and then work to make sure they’re taken care of.

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

Transforming Our Systems to Meet Students Where They Are

Once we agree that it’s our job to ask our students what they need and then meet those needs, we understand we need to change the ways our institutions (in this case schools) respond to those students. We need to change our systems to support students rather than to discipline them.

What do we mean when we talk about systems change? Systems are built by people, informed by our culture—our values and beliefs. Jason shared with us the guiding principles of building effective, responsive systems for students:

- Enhancing student satisfaction is key to improving student performance.

- Transparency builds and sustains trust.

- Collective input from all stakeholders throughout the process is critical.

- Cultural norms must support wellness and livelihood.

We dug deeper by getting curious about four key elements of a school:

- Environment.

- Climate. How can we create an experience at school? What does it feel like to be here?

- Culture. What are our rituals when we arrive? How are we welcoming people? Is it supportive and loving?

- Aesthetics. What do we see? What’s on the walls? All these visual elements create and support ideas.

- Ethos

- Guiding beliefs. Are we assets-based? What do we believe is possible here? Can we get curious?

- Values and ideas. What’s the emotional tone of the school? Does this vibe and energy support growth and development?

- Relationships

- Community. How are we building it and inviting others in? Do we share knowledge and skills?

- Connectedness. How are we relating to each other at all levels (teachers, students, parents, administrators, staff)? How are we speaking to one another? Are we one team?

- Governance

- Policies and practice. How do these support our values and beliefs? Are we relying on old muscle-memory?

- Power and decision-making. What kind of trust is present in our classroom rules?

- Curriculum. Are our lessons culturally responsive and culturally sustaining? Are they relating the content to young people’s lived experiences?

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

The Need

Chatham County has the most robust and destructive school-to-prison pipeline in our state: we have nearly twice as many court-involved young people as any other county in Georgia, including Atlanta’s Fulton County. After our police department, the SCCPSS is the biggest referrer of young people to court.

These numbers tell us more about ourselves and our systems than about our young people. Our children are not twice as bad as Atlanta’s kids. Our numbers are so high because our child-serving institutions—severely under-resourced and relying on old, dehumanizing narratives about working-class families and youth of color—are disciplining young people when they should be meeting them at their stories and addressing their unique needs. This can be seen most strikingly in how Savannah chooses to allocate resources for children in need: to courts and police rather than mental health, education, enrichment programs, and other services that foster healthy development. The culture in which Savannah’s young people are immersed is one of punishment rather than restoration and care. And the ways punishment is applied do not account for history, systemic harms, and the often-traumatizing daily experiences of growing up in Savannah.

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

Calling in to Community

To address Chatham County’s dire need, Healing Schools will create a new way of doing things. Deep’s approach is strongly inspired by the work of educator and activist Dr. Shawn Ginwright, who has encouraged an evolution away from “trauma-informed care” to an assets-based, systems-level approach he calls “healing-centered engagement.”

The grounding assumption of Healing Schools’ whole-village approach is this: that to heal one part of the body, we will need to understand the whole. The ultimate goal of Healing Schools is to prepare students to be engaged, thriving participants in our democracy and communities by making sure they have the resources they need, are celebrated and served according to who and where they are, and are lifted up with their families and teachers as leaders able to participate in determining how their schools meet their needs.

With this in mind, the Healing Schools model will:

- recognize and respond to young people’s trauma with love and restoration, and with the overarching goal of keeping students in our school community rather than pushing them into disciplinary settings that harm them;

- use an equity lens that addresses implicit bias in regard to race, class, and related structural barriers;

- engage students, teachers, staff, and families in working to reform and dismantle harmful systems that make it hard for young people to succeed and thrive.

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

An Open Heart, a New Toolkit

As we closed out the day, this group of teachers, administrators, nutrition specialists, paraprofessionals, students, and parents left, paradoxically, both more tender and more resilient. This skill at opening up their hearts as a source of power will be crucial for the work that lies ahead.

Who were you as a young person? What did you need? What did you need, and how did it enable you to thrive? What can you bring into your role at Hubert, right now, to shift the climate towards one of healing and relationships?

Photo by Somi Benson-Jaja

Answering these questions has given the Hubert community the beginning of a new toolkit, one that will enable the adults in the building to show up for their students as their full-hearted, flawed, but determined selves. In this way, Healing Schools is making it possible for educators to change not only the way school climate looks for Chatham County’s young people, but how our community shows up for our children in general.

Shawn Ginwright describes the job of the educator as a transformative presence:

…our job is to defend and dream, resist and reimagine, disrupt and discover. While we cannot expect the quick solution to come in our lifetime, we can, each day, prepare our young people for a more beautiful struggle in theirs.

Deep Center’s Healing Schools initiative is made possible by funding through The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through Forward Promise, and through a partnership with the Savannah Chatham County Public Schools System.