This blog post, written by Community Engagement Coordinator Raphael Eissa, is the fifth in an ongoing series, 10 Years Deep, that celebrates the evolution and growth of Deep Center’s programs in our first decade.

(Read all posts in the 10 Years Deep series here.)

(Read part 2, “Youth Summit Presents the Work,” here)

At Deep, we use creative writing and the arts to help young people connect their learning to their lives, their lives to their communities, and their actions to transformational change. Deep learning is connected learning that nurtures creativity, play, and building power in the world. We make learning purposeful, personal, and truthful by embedding it in the neighborhoods we come from and the stories of the people living there. And because Savannah’s young people understand that the many barriers they face to success are not of their own creation, our Action Research Team is conducting research and generating actionable data that Deep’s community will use to advocate for change.

Photo: Laura Mulder

“ One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted. The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.” – James Baldwin, The Creative Process

Lessons from My Friend James*

Long before I was the community engagement coordinator at Deep Center, I was a student at Islands High School. I first met my close friend James in my AP American Government class at Islands. James is and was a person who deeply valued inquiry. His boundless capacity to wonder and question meant that he was always challenging the status quo and asking hard questions in class. But our teacher didn’t entertain them, and usually insisted we move on.

The unfortunate lesson James and I learned in our AP class was that questions that got to the root of the matter—or those that challenged authority—were too often dismissed or simply considered disruptive. We learned that curiosity is not always welcome and that learning is not, in fact, always the main objective in our classrooms.

As one of the co-facilitators of Deep Center’s Action Research Team (ART), I stand with young people as they seek to discover and ask difficult questions about the people and systems in their lives making decisions that affect their communities. One of the main ways we do this is through a process called Youth Participatory Action Research.

Defining YPAR

“Youth Participatory Action Research” or “YPAR” can be a mouthful, but it describes a process that is simple, accessible, and empowering for our communities.

YPAR is the purpose of Deep’s Action Research Team (one of pathways, alongside the Slam Team, for Deep’s Youth Leadership Team). ART consists of up to six young leaders who have completed Block by Block and are excited to throw themselves headfirst into researching Savannah. They take to the streets not just as researchers, but also as artists, creative writers, and organizers, to identify and understand the policies and systems affecting our communities.

YPAR is a process of research and community engagement that enables youth to unpack Savannah’s past and present, speak out on critical issues affecting their families, friends, and neighborhoods, and ultimately transform Savannah. Too often, the image of a “researcher” comes from outdated stereotypes, which makes it hard for most of us outside of academia to identify with that role. Participatory action research says that we are all the experts of our own experiences, that the status of researcher is a malleable one, that power should be deliberately shared between the researcher and the research subjects, that communities should own their own data, and that the goal of research is, ultimately, to understand and improve the world around us. YPAR encourages community members, including young people in particular, to engage collectively, and look internally, in both inquiry and the advancement of solutions to societal issues.

Photo: Laura Mulder

Think of It Like This

YPAR is research reimagined so that everyone can do it. YPAR is a practical and accessible tool for youth and families to understand and name what is and isn’t working in the systems that determine how their worlds function, so that they can change their communities for the better.

People in the community, and in Deep’s case, young people, are central to this practice, from design to action to conclusion. To paraphrase community organizer and scholar Shawn Ginwright in his essay, The Future of Healing: Shifting From Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement, YPAR serves as a research process that transcends the barriers between the artist and the scholar, especially when young people are given the tools to explore their communities and the stories that are embedded in them to name the forms of oppression surrounding them, and subsequently to transform those conditions.

The People Aren’t the Problem: the Problem Is the Problem

When we think about and tell stories about young people and the challenges they face growing up, we too often fixate on individual people succeeding or failing, and we assign blame or credit accordingly. We assume people are the problem. Are her parents around? Do her parents love her enough? Discipline her enough? What values are the parents instilling in her? Is she lazy or hardworking? Does she have healthy role models teaching her the importance of a job? Do her teachers care?

Telling the story this way, however, ignores the historical realities and structural inequities underpinning the barriers that most young people encounter. Thus, the value of YPAR lies in its ability to encourage participants to see that “the people aren’t the problem, the problem is the problem.” YPAR both enables youth participants to take charge of their lives, and throws the focus where it ought to be: on systemic issues. With YPAR, youth interrogate these overly-simplified narratives, understand the systemic pressures impeding their everyday lives, and work proactively to fix these problems.

In this sense, YPAR helps youth recognize “what was” and “what is” as mediums for “what can be.”

Photo: Laura Mulder

Naming the Change We Need

Imagine if my friend James had the opportunity to question what was “normal” without being dismissed or shamed. Imagine if educators had the support and resources that enabled them to make the time truly to explore the questions students ask, even if they may throw off the day’s lesson. What if my teacher had been equipped with culturally-relevant curricula and had been able to walk with James and me through the abstract wilderness of our creativity.

My lived experience, and the work of ART, both suggest that Savannah has a culture of not listening to young people when they speak up and not honoring young people with experiences and identities that don’t fit neatly into what’s considered “normal.” We believe there is a direct link between this culture and the fact that Chatham County, according to the data, over-disciplines young people. Chatham County has nearly twice the number of court-involved youth as any other county in Georgia, and our juvenile justice system disproportionately hurts black and brown youth. According to the Civils Rights Data Collection Discipline report, African American children make up a disproportionate percentage public school students receiving disciplinary actions in Chatham County. In that same year, 5,034 students were expelled as a result of zero-tolerance policies. Furthermore, black boys are six times more likely to be referred to court than white boys.

I have met many young people during the ART research process who are living inside of this set of challenges. One young man, who is systems-involved, referred to himself as a “client” of his probation officer. Imagine how taking on the name “client” is shaping the stories he tells about himself.

ART’s research is asking: How can we give young people tools that celebrate their curiosity and imagination while giving them more autonomy, more information, and more ways to show up and advocate for the story of who they truly are?

How Deep Is Doing This

In 2015, Deep Executive Director Dare Dukes authored an article entitled “How Creative Writers Will Save the World.” Four years later, the piece still rings true. Deep is all about creativity, and we’re all about employing that creativity beyond the confines of what the status quo says is acceptable. That’s why members of ART are currently in the throes of researching and illustrating what it’s like to grow up, and often to be harmed, in Savannah—by Savannah.

For Deep, that means creating a space wherein a multiplicity of experiences, identities, and privileges come together—and not always necessarily with grace—to interrogate where we stand in relation to others.

As one of the co-facilitators of this process, I called and texted and messaged on Facebook. I dropped by and made my way between secretaries and church leaders, moms and aunties. In recognizing that there are many kinds of people and experiences who must be accounted for in the work they’d be doing, ART members prepared to enter a space that might, at times, feel uncomfortable, but would always feel real.

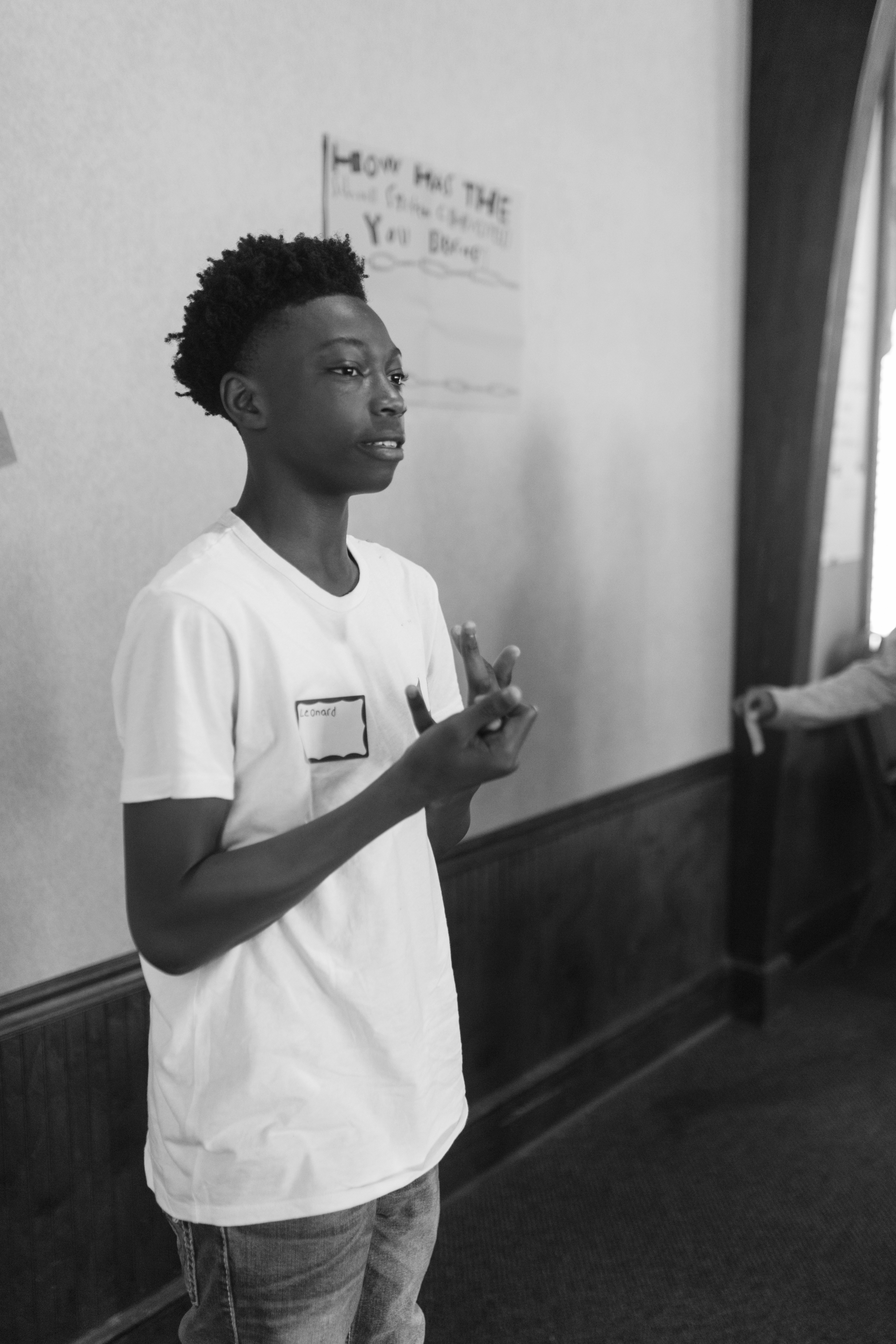

Throughout 2019, Deep has hosted a multi-part Youth Summit. Young people from around the city have been gathering to examine the world that they live in and figure out the things they can do to transform it. In this learning space, we named the system this work will upend: the school-to-prison pipeline, which includes policies, rules, regulations, and practices that push young people out of school and into the systems that irreparably harm them, such as the juvenile justice system.

Photo: Laura Mulder

The People Closest to the Problem Are Closest to the Solution

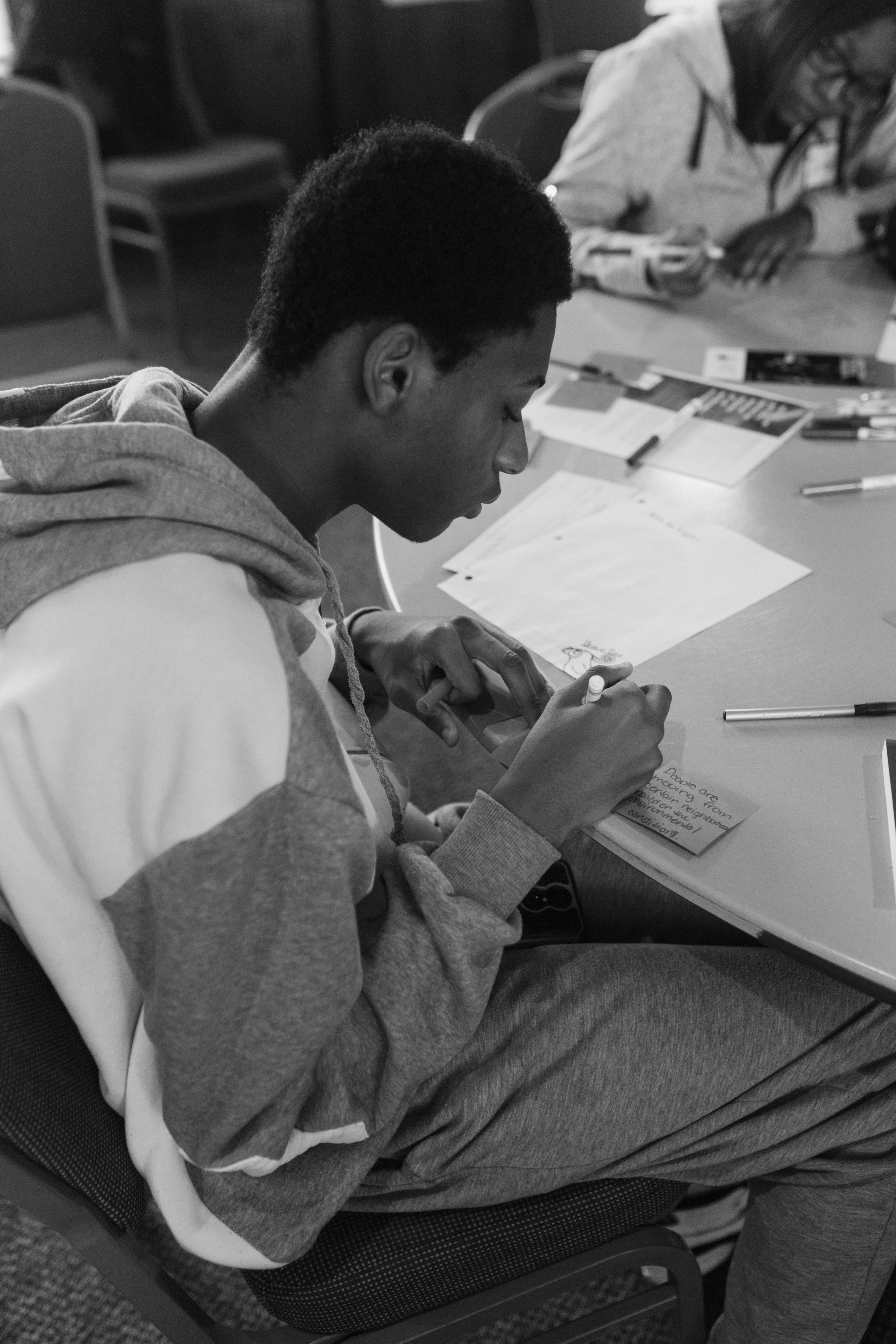

In early October, research that ART developed will inform the debut of Deep’s first-ever policy brief—a tool for reform created for and by Savannah’s young people. The brief will enable Deep to invite stakeholders and elected leaders to learn about what Savannah’s young people need the most. ART has wrapped up their final round of research and begun to present the data to Savannah’s community stakeholders. They are now in the process of listening to community feedback and finding where they can expand or edit, push for more or dig deeper.

Come October, they will have a year’s worth of research and a policy brief that says to Savannah: “We can create the change, and we are the change we seek.”

Photo: Laura Mulder

Continue on to part 2, “Youth Summit Presents the Work,” here.

* Name has been changed for privacy